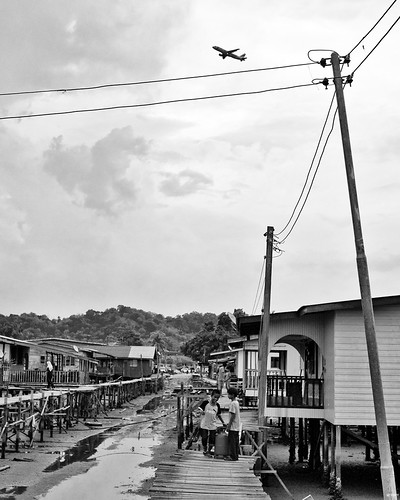

As Air Asia takes to the skies above Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, East Malaysia (formerly known as British North Borneo), the passengers undoubtedtly take in the sights of the nearby Tunku Abdul Rahman Park, a small marine sanctuary right off the coast of this small, yet distinctly urban capital city. Right below the flight path, not a mile from the northern end of the runway (part of a RM1.4 billion extension and expansion programme), lies a virtual suburb occupying prime real estate, extending out to sea, and built on wooden stilts. Here exists in Tanjung Aru, nestled between 5-star resorts, a world-class private marina and night-game equipped golf course, a confirmed slum.

It would seem that the further a city or territory lies from mainland Malaysia, the less attention is paid to fine details such as basic human necessities. Generations have bred, lived and died in this microcosm of Malaysia itself. Tribes and races co-exist side by side in a proximity and density not experienced by the majority of the country's citizens. It was once a thriving and recognised residential district, serving as a base for the local fishing fleet. Today, while semi-legal, it is bereft of ammenities such as waste and sewerage disposal.

Yet it continues to exist, evolving over time as the community it houses changes according to the local socio-economic influences.

On the peninsular, low-cost government housing is readily provided. Here, children transport tanks of gas in order to help out with the family income, and as play and entertainment. They race around the labyrinth of timber ramps and bridges at impossible speed, deftly maneuvering their metal charges with responsive hands and feet working together in graceful rhythm. The search for the national F1 squad's drivers could begin here.

There are signs of impending improvement to the conditions, but the skeletons of steel reinforcement and abruptly halted concrete pours hint at the reality behind the promises. Prior to the last elections in 2008, the entire kampung was slated for wholesale redevelopment aimed at reinventing the slum into a tourist attraction, harking to the maritime tradition of the city for inspiration. With the overwhelming victory achieved by the ruling party, the project stalled to become an insipid quagmire of glacial progress. The money somehow ceased to be available.

Homes were marked for demolition and replacement. Some have been torn down but never re-built. Dwellers wait for the promised change, while the children continue on their way, their innocence shielding them from their parents' concerns.

Life here seems to ebb and flow with the ever present tide. As the sea rises, the mud and trash are covered and swept aside, only to return 12 hours later. The terrain under the boardwalks is uncertain due to the actions of the sea and winds. This is reflected in the lives and tokens of the slums' inhabitants. One person's unwanted relics become another person's toy or tool. To the visitor, time capsules open periodically to provide remembrances of things past.

The people who live here are called by many names. Kadazan, Dusun, Bajau, Hakka, Melayu, Indo, Filipino are only some of them. Ja'afar, Henry, Paulus, Chin are more specific, but none serve to define who they are. They are forgotten when not needed, and courted at times when it matters to be counted.

No comments:

Post a Comment